Paul Fairie is a political scientist at the University of Calgary, where he studies voter behaviour.

The federal election is scheduled for a year away and every political scientist is being asked the same question: who is going to win? Other than coming up with creative ways to avoid answering the question, we instead can attempt to make some predictions by consulting two prominent psephological soothsayers: opinion polls, and the economy.

Public opinion polls: better than a random number generator?

Despite some recent problems predicting the recent Alberta and British Columbia provincial elections, opinion polls are still generally seen as reliable indicators of public sentiment about politics. Can they tell us anything about elections an entire year away?

To informally test this, I looked for polls in the archives from as close to a year from the elections between 1984 and 2011 as I could find. Including elections before this point in time presents the awkward problem of the 1980 vote being held less than 14 months after the 1979 election. While a weighted average of a number of polls might be better to reduce the influence of a rogue poll, this one poll method will have to suffice in the absence of a comprehensive elections database.

Looking at these numbers, it’s clear that only relying on polls a year out doesn’t give up a good idea as to what’s going to happen a year from now. Sometimes they have provided good visions of the future: the huge PC majority in 1984 was clear a year before the election. However, polls in 1987 would have forecast the PCs as third in 1988, completely missing their comfortable majority victory. Polls a year out would have called larger majorities for the Liberals between 1993 and 2000 than they ended up winning, as well as a comfortable win in 2004 when they won a minority.

However, expecting polls to have such forecasting power is unfair, as they are taking a snapshot of what would happen if an election were held today, not a year from now. This is understandable: I have enough difficulty deciding what to have for dinner tonight. I can’t imagine picking what I might want to have a year from now. It’s not that polls aren’t good predictors of elections; it’s that they aren’t good predictors of Canadian elections a year from now.

The economy

Research into the connections between elections and economics has repeatedly shown that incumbent governments generally do well when the economy is good, and are frequently punished when economic performance is poor. This makes a great deal of sense – voters evaluate governments on their performance, and the performance of the economy is one that people can feel viscerally.

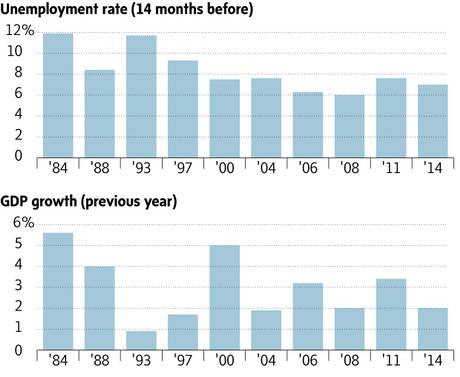

Two economic indicators tend to dominate the public interest: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth, and the unemployment rate. World Bank numbers suggest that GDP growth in Canada was 2 per cent in 2013. Can this tell us anything about the election next year? Comparing the numbers in the above chart to the change in vote an incumbent government received the next year suggests there isn’t a relationship between this measure of economic activity and election results. High GDP growth doesn’t correspond to either a good or bad performance by the incumbent.

What about the unemployment rate? The last report from the Labour Force Survey measured the August 2014 unemployment rate at 7 per cent. In order to determine if this statistic foretells good or bad fortune for the Conservatives, we need to look at similar unemployment rate reports from 14 months before elections in past years to see if they match up with the changes in levels of government support at election time.

Consistent with research in Canada and elsewhere, these nine elections do suggest that there is some relationship between the unemployment rate 14 months before an election and the subsequent change in government support from voters. For example, the two elections with unusually high unemployment rates (1984 at 11.9 per cent and 1993 at 11.7 per cent) were the also the two elections with the most disastrous performances for incumbent governments in recent memory. While surely other factors also affected the results, such as the emergence of new parties in 1993, unemployment rates greater than 11 per cent certainly didn’t help the chances of John Turner’s Liberals, or the Progressive Conservatives led by Kim Campbell.

The forecast for 2015

What does this suggest for the Harper-led Conservatives? Let’s look at the possible impact of the most reliable of these three simple indicators: the unemployment rate. The recently reported 7 per cent unemployment rate was actually quite good news for their chances in 2015. Looking at other elections where the unemployment rate sat near 7 per cent, we can notice that governments more or less held on to their vote from the previous election. Looking just at elections where unemployment was between 6 and 8 per cent, we can see that incumbent performance ranges from a 6.5 per cent loss to a 2 per cent gain in the popular vote. Taking the average of these votes suggests a slight decline, perhaps one or two per cent, in the Conservative vote in 2015.

However, opinion polls taken in the last month suggest that the Conservatives are polling at around 31 per cent nationally, almost 9 per cent lower than their performance in 2011. What might account for this difference from the economic forecast? If you are a Conservative optimist, you might believe this means that the Conservatives have good room for growth going forward. If, instead, you think that the polls are a good indication of public sentiment towards the government, it might suggest that other factors (such as dissatisfaction with non-economic aspects of Conservative performance, Trudeaumania 2.0, or simply just fatigue with the incumbent government) might be bringing levels of Conservative support down.

Of course, while economic indicators can influence election results, they do not alone determine election outcomes. Public opinion and election results are complex phenomena that are difficult to model correctly. Many factors can change for the Conservatives between now and October 2015. Public fatigue with the incumbent government might grow worse, the election campaign might go exceptionally well or poorly, and the most dastardly factor of all might even make itself known, rendering even the most talented election psychic prediction-less: the spectre of unexpected events.

If you met the federal party leaders on the campaign trail, what would you ask them? Post your question to Facebook, or Tweet or Vine it with #VoteCountdown. Take a look at what readers have already suggested.