In a fresh white lab coat, his name embroidered atop a chest pocket, Cameron Miller looks and sounds every bit the chemist that he is. When he begins talking about the wonders of terpenes - the organic compounds that give plants their distinct odour - he could be a sommelier discussing the power and influence that tannins have on wine.

“Rosemary and oregano, for example, have some very unique terpene profiles,” says Mr. Miller, lab manager at The Werc Shop. “Very, very pungent. You identify instantly with the scent. Terpenes can be very rich and powerful, in their presentation. Intricate, complex and beautiful too.”

Among Mr. Miller’s favourite terpene-producing plants is one he happens to handle every day: cannabis. It has an amazing variety of aromas, he insists, ones he’s not particularly adept at describing but which nonetheless interest him far more than the element of pot that seizes the imagination of most users: potency.

While it has been two years since Washington State voters approved Initiative 502, which legalized marijuana, it has only been nine months since the first retail outlets opened. There have been some early growing pains. And one of the areas that has come under intense scrutiny is the system being used to measure the strength of the pot hitting the market.

There are state officials, lab technicians and state-approved sellers who suspect samples are being tampered with either before or during the sampling process. There’s been the suggestion some growers are “spiking” their samples to give them higher levels of tetrahydrocannabinol – or THC – the chemical responsible for most of cannabis’s psychological effects.

The higher the level of THC, the more the grower is able to charge for his crop, and the more retailers can charge at the counter. Some labs have reported THC levels in the 30 to 40 per cent range – a number that defies possibility in many people’s minds. Most marijuana contains THC levels ranging in the mid-teens to the mid-to-high 20s.

Randy Simmons, marijuana project director for the state, believes some cannabis producers are manipulating their samples before handing them over to a lab for inspection. There is a broad suspicion this is being done by spraying the test product with hash oil or dipping it in ‘kief’ – a powder derived from the buds of the marijuana plant. Both actions will boost the traceable amounts of THC. There is also thinking that growers are cherry-picking the very best buds to send off for inspection, again helping to produce a THC number that doesn’t reflect that of the overall crop.

“Part of the issue is right now we leave it up to the growers to produce the sample to the lab and I’m not sure that is what we want to do,” said Mr. Simmons.

The state-approved marijuana testing labs depend on the growers for their business. If the producers don’t like the results they’re getting at Lab A they can take their business to Lab B – creating an essential struggle at the centre of the testing system.

Brad Douglass, the scientific director at The Werc Shop, agrees that there is a financial incentive for labs to game the system on behalf of their customers.

“We think it’s just the way the market is currently set up where the product is currently being valued by percentage of THC,” he said in an interview. “Anytime you have an incentive like that there’s a good chance some people will act on the incentive.”

The Werc Shop was formerly a cancer research laboratory that went out of business. But Werc was able to use much of the high-end equipment that came with the premises, including liquid and gas chromatographs. The shelves are lined with beakers and crucibles, droppers and graduated cylinders. A nearby white board contains words that are foreign to most of us: Spilanthol, Acitral, quassin. There are diagrams of chemical compounds. A sample of marijuana brownies sit in a sterile plastic bag waiting for testing.

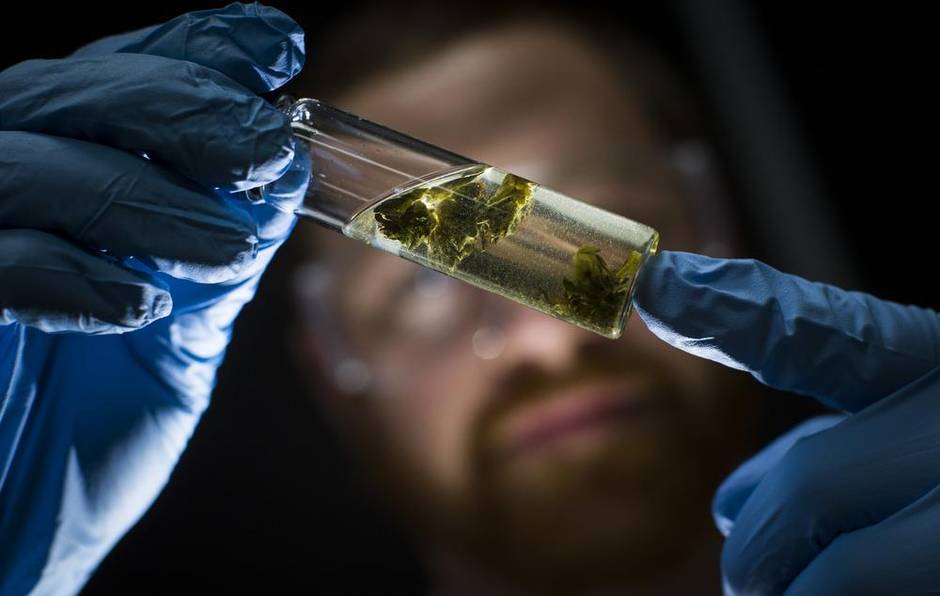

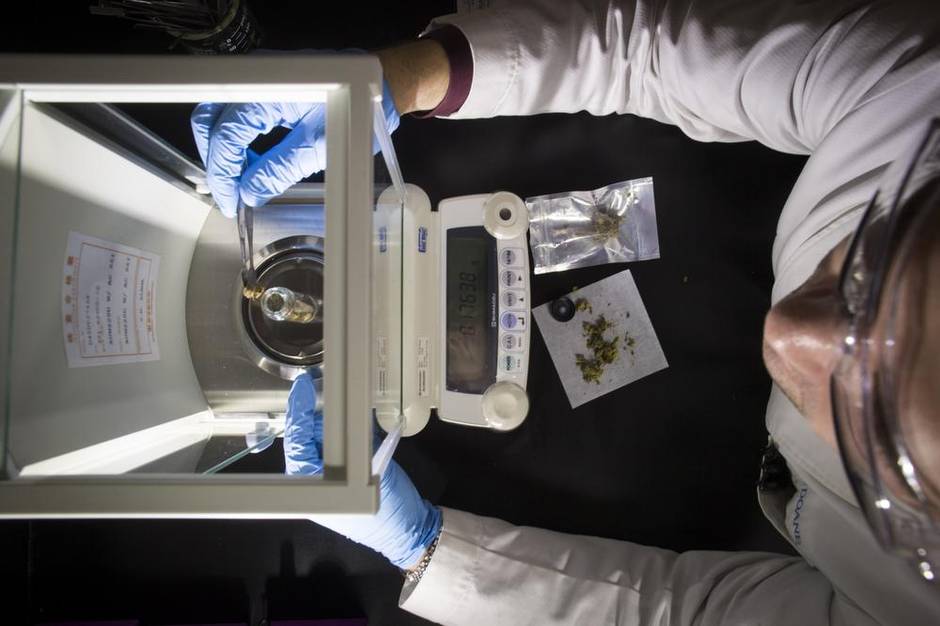

When a cannabis sample arrives at the lab, it is first weighed and inspected for yeast, mould or other harmful substances. To test for potency, the cannabis is placed in a tube with a solvent that allows the chemical elements to detach as the tube spins in a centrifuge. After that, one part of the same goes in the liquid chromatograph, another in its gas counterpart. UV lamps are later used to distinguish what chemicals are present, including the marijuana’s terpene and cannabinoid profile.

There is believed to be nearly 500 natural components contained in a cannabis plant, of which nearly 70 are unique to marijuana. These are known as cannabinoids, the most famous being THC, which is primarily responsible for the plant’s psychoactive effects on people. Even though a chemical found in marijuana known as cannabidiol (CBD) is believed to contain many of the plant’s medicinal powers, it’s still THC that the common user – and grower - is after.

The Washington State Liquor Board, which oversees the legalized marijuana market, is now exploring different means of eliminating the possibility of lab samples being “juiced” by growers prior to testing and ensuring the accuracy of the tests themselves.

“We have started a secret shopper program,” marijuana project director Mr. Simmons said in an interview. “This is where we got out and buy something off the retail shelf and get it tested by an independent lab. If there is a discrepancy between that result and the information [THC levels] on the package that was sold to our secret shopper than we go back to the lab that did the testing for it and we go to the grower involved to see what’s up.”

Mr. Simmons says his department now has staff that is doing nothing but monitoring the content of the pot being sold.

“We’re seeing strengths here that you don’t see anywhere else in the world which is impossible. It’s a plant. It’s going to do what a plant does. We need to get control over what’s happening that should not be happening.”

The state is also considering new ways of obtaining the marijuana samples at the front end of the testing system, taking that part of the procedure out of the hands of growers and putting it into ones owned by an independent arbiter. As well, the liquor board is also cognizant that some of the discrepancies in testing results could be the fault of the lab and the result of faulty equipment or sloppy procedures.

Some lab leaders would like to see far more oversight of the lab work and have even suggested imposing a validated methodology on the companies. That would mean the labs would all have to abide by the same testing protocol, using the same equipment.

Back at the lab, Cameron Miller talks about where he hopes the marijuana industry heads. One day, he imagines people walking into cannabis outlets far more interested in strains that smell and taste good than stuff that renders you near paralyzed by high THC content.

“I’d like to see the market geared towards more of a wine crowd,” he said. “One that has a more sophisticated palate for marijuana and is not just focused on potency. That’s my eventual hope anyway.”