Quebec's design and architecture scene is among the most dynamic in Canada, supported by a robust manufacturing sector and a cultural willingness among both clients and distributors to experiment. Who is doing the best work right now? Globe Style spotlights five hot talents to watch, from a master in the medium of concrete to the maker of impossibly sculptural seating.

Henri Cleinge Architect

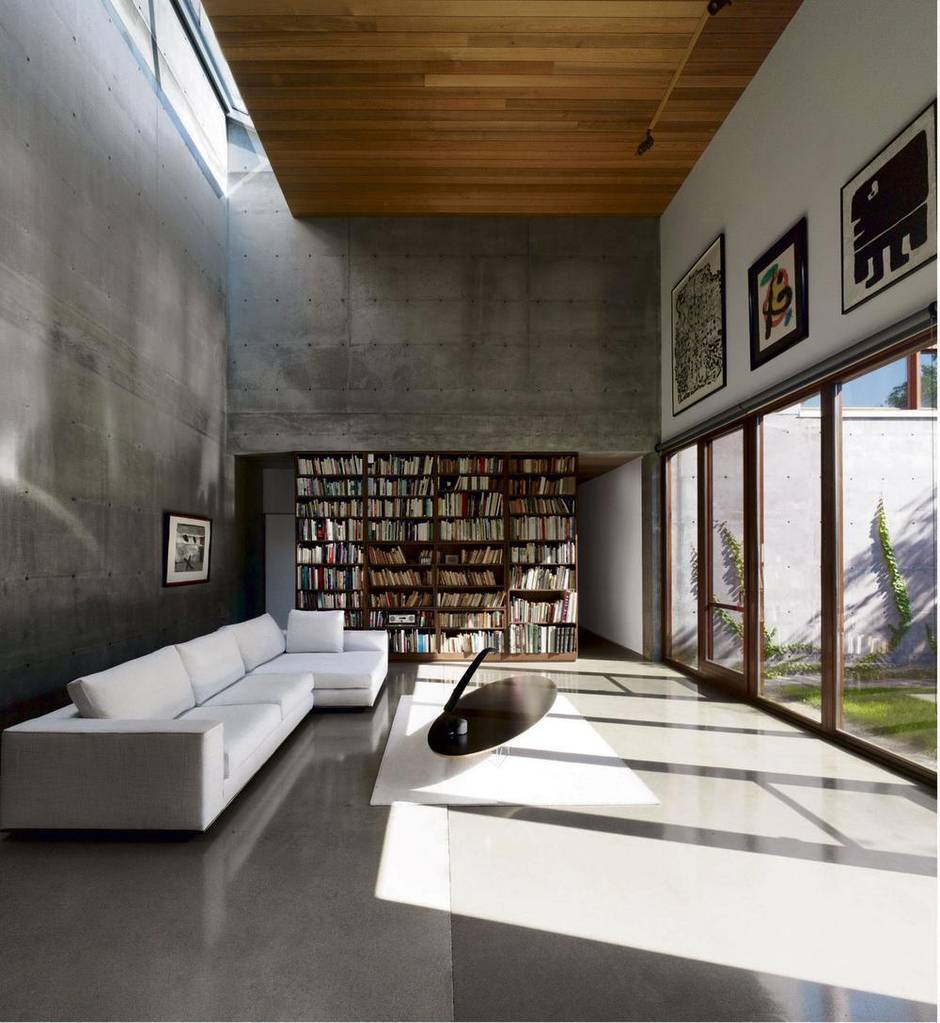

Concrete in architecture is similar to rice in a restaurant: an entirely prosaic ingredient that, in the wrong hands, can be offensively dry and bland. But with creativity, both can be brilliant. Montreal-based architect Henri Cleinge knows how to bring out the best in the material. His own, recently completed home is an excellent example. It’s cast in the grey stuff, but looks airy and warm. That’s because the Carleton University grad punched the roof with skylights, so the walls are raked with a glowing, southwesterly light. He also selectively layered in other elements, like Corten steel window frames, cedar ceilings and a maplewood staircase. The concrete, in this context, acts as a subtle backdrop for the contrasting materials to pop against. The same deftness with balance comes out in other areas of Cleinge’s practice as well. A home he designed in Dorval, for example, offsets a historic stone home with a contemporary steel addition, but does so in a way that makes the whole, unified composition look cohesive and complete. www.cleinge.com.

Loïc Bard

Montreal-based furniture designer Loïc Bard does things with his favourite wood, Canadian maple, that seem impossible for the material. His series of Tokyo tables, for example, have the kind of curves more often associated with plastic (one has a rounded slot for magazines that could be the hatch for an alien space vessel), while his Chicago table has the type of swoops, curves and bends more commonly seen on a Frank Gehry building. It’s all very futuristic and highly cool. Yet, interestingly, it all has roots in Bard’s own past. He was raised in a small village in France, where woodworking was his hobby. And he discovered Canadian maple as a design student at Montreal’s École d’Ébénisterie d’Art, from which he graduated in 2012. Each piece also has a highly personal back story: The aforementioned Tokyo tables were built after an inspirational trip to Japan. Likewise, many of his other works are named after the friends and places that have helped inform his unique, idiosyncratic style. www.loicbard.com.

Zoë Mowat Design

Some furniture designers approach their pieces as though they are creating art to be admired, not functional objects to be sat on, slept on or trod all over. Alberta-born, Montreal-based Zoë Mowat strives for something much more pragmatic – utilitarian stuff that helps make living easier. Her Tablescape tables, for instance, are a multitasker’s dream: They have built-in bookends, pencil cases and potholders. Likewise, her complementary Cache series of credenzas and organizers have plenty of drawers and doors to tuck away linens and plates and whatever else needs hiding. In fact, storage cabinets, the least sexy thing a furniture designer can tackle, are her specialty. Part of the appeal for Mowat in crafting such pieces is the challenge of elevating the everyday into something extraordinary. She does so by defining even the most functional furniture through unusual mixes of materials (such as walnut and felt) and surprising colours – juxtapositions that add a much-desired sculptural quality. www.zoemowat.com.

Lambert et Fils

In 2010, when Samuel Lambert decided to make the transition from post-production on films to industrial design (to engage in less paper-pushing and more playful craftsmanship, he says), he started by refurbishing old lamps from his favourite eras: the 1940s, fifties and sixties. Four years later, his brand, Lambert & Fils, has grown from a one-person operation to a 12-person studio with a boutique on Montreal’s Beaubien Street. And he no longer uses vintage parts in his entirely original lighting creations, which have been collected by discerning homeowners around the world. But his pieces still have a touch of nostalgia for mid-century modernism. He often starts by referencing the classic lines and looks of the period (the Taschen book, 1000 Lights, is a go-to source of inspiration) and he often uses brass because it develops an antique-looking patina. But he also updates and contemporizes the forms – by using sleek, luxurious marble bases, say, or his signature, chic black shades. www.lambertetfils.squarespace.com.

Naturehumaine

Young architects starting out often find their footing with unconventional clients. When Stéphane Rasselet co-founded his studio, Naturehumaine, about 10 years ago, one his first big commissions was for the Memoria line of funeral homes. Rasselet, a McGill graduate who had by then worked in various firms in Quebec and France, upended the conventions of a mortuary: Instead of making his cloistered, dark and solemn, he flooded the spaces with light, so each room would inspire a celebration of life. Although his studio now works mainly on private homes, which constitute 85 per cent of his commissions, he still embraces a certain amount of strangeness and a lot of invention in each project. He clad the back of one home with bright yellow and green paneling, for example, to bring life to the adjacent alleyway. And he shaped the siding around the window of another home to look like a giant oculus peering into the background. Such gestures help to lend his work a certain signature, but they also give people who see his spaces a sense of surprise and a reminder that creativity can be found even in unlikely places. www.naturehumaine.com.