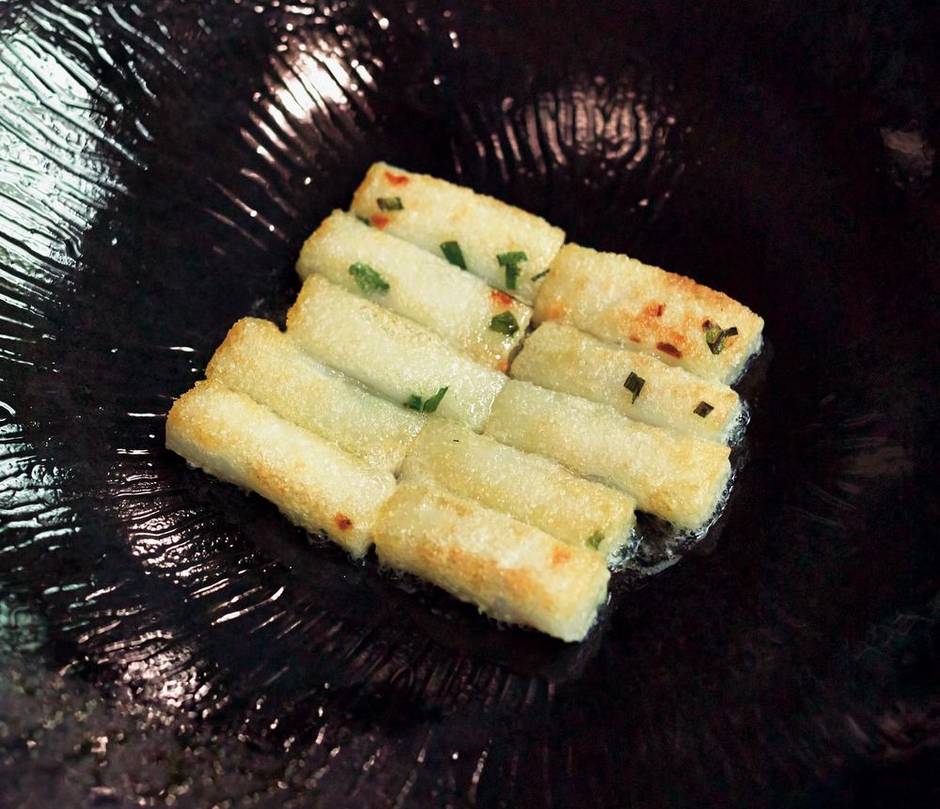

T’ang Court’s dining room is as gold-plated fancy as they come. Located inside Hong Kong’s ritzy Langham Hotel – and next door to flagships for Cartier, Miu Miu and Ermenegildo Zegna – it’s outfitted with white heirloom orchids, velvet brocade curtains and antique sculptures of horses posing under beams of halogen light. The menu is equally posh, featuring abalone, bird’s nest and other Asian delicacies. The best dish on offer at T’ang Court, however, isn’t listed on the menu and isn’t luxurious in the least. It’s the humble Cantonese standby known as chee cheong fun.

The rice rolls are made with flat sheets of noodles that have been curled up and pan-fried, giving their exterior a golden-brown crust. Crispy on the outside, gooey tender on the inside and equally silky and salty, their texture is reason enough to travel to HK. They’re the sort of staple you can find on any local diner menu or at dai pai dongs, the open-air stalls where skewers of meat, kidneys, intestines and other wobbly gaskets steam away on the side of busy intersections. Their appearance at T’ang Court illustrates how that culture is increasingly influencing what’s on offer at the city’s higher-end establishments, and vice versa.

I have come to Hong Kong for two reasons. I’m here to explore the connection between high and low cuisine in the city’s restaurant scene, but also to contemplate the ways that food writers such as myself discover amazing meals in far-flung cities, especially at local dives that rarely register a TripAdvisor rating.

Hong Kong is ideally suited for such a pursuit. Not only do people fly here just to eat, the city is relatively easy to navigate, thanks to its British colonial history. HK also has a particularly high concentration of superb restaurants. The way people eat in Hong Kong says so much about the city itself. Because space is at such a premium, apartments here – and, by extension, kitchens – are tiny.

As a result, people eat out often, a phenomenon helped by the fact that you can eat very well here for very little money. As long as you know the phrase ho bau, Cantonese for “very full,” you’ll do just fine.

You feel very full often in Hong King, especially because you are constantly snacking on things like chee cheong fun. T’ang Court Master Chef Kwong Wai Keung says that his iteration is “less oily” than others, which didn’t seem to me to be the case, as oiliness is kind of the point of the addictive bites. They may taste slightly cleaner than the norm, as well as a tad crispier, but even in these hallowed precincts, the rolls remain a homey pleasure. To accentuate the overlap between street and haute, Keung pairs them with house-made XO sauce, a high-end Hong Kong original created in Kowloon. The garlicky chili mélange spiked with nuggets of Jinhua ham and dried scallop takes its name from the cachet of XO Cognac, and dates back to the early 1980s, when the colony enjoyed a period of particular affluence.

On the inverse side of the high-low spectrum, no place captures the meeting of down-home atmosphere with stratospheric price tags like Sheung Hing Chiu Chow, a restaurant on Queen’s Road West.

The restaurant’s star attraction is its cold roasted goose breast, served atop tofu marinated in what the owner calls “15-year-old sauce.” You dip the pieces of chilled fatty, salty poultry into delicate pink vinegar to cut its richness. It goes surprisingly well with the restaurant’s other specialty, cold flower crab. The red leopard print crabs are sold by the weight and even a small one will set you back the equivalent of $250.

Sheung Hing Chiu Chow is a place for people who know how to eat and who have the resources to do so in style. It’s one of the favourite haunts of the wealthiest man in China, Alibaba CEO Jack Ma.

“Why is this place so incredibly good?” I ask the owner at the end of my meal, not really expecting a response. “Because this is where Hong Kong’s culinary heritage is being preserved,” he told me.

Consuming humbler examples of that culinary heritage – in the form of almost transparent har gao (shrimp dumplings) or the glossiest char siu (barbecued pork) – in a lowly dive that’s a local favourite can be tricky for visitors in town for a short trip. Consulting food-review sites can be helpful, but many of them are seeded with fake opinions (still, several Hong Kong food writers told me that OpenRice.com is the one they use for tips). In the end, nothing beats talking to a local.

My colleague Chris Nuttall-Smith, The Globe and Mail’s food critic, put me in touch with some friends in Hong Kong who brought me to one of their favourite places, Leung Kee in Sai Wan Ho. The restaurant is next to a fish market, so you can pick live seafood from the fishmongers and have the chefs prepare it to order. The steamed rock grouper we had made for one of the freshest, most flavourful meals I’ve ever experienced.

Signing up for a tour is also an option. I personally dislike guided tours, but if you don’t mind being herded along in a group, try Hong Kong Foodie Tasting Tour. Two of the meat joints highlighted on their itineraries are Yung Kee Restaurant on Wellington Street and Dragon Restaurant on Queen Victoria Street, both of which qualify for “die, die, must try” status among residents.

Of course, you can always follow the lineups. A queue usually indicates good things, although sometimes they are just too long. One morning, I walked past a place called Australia Dairy Co. where the wait time for a breakfast of thin, watery broth with elbow macaroni and ham was more than an hour. “It’s kind of terrible, but also great,” a patient diner told me.

Or there’s always Google. Searching “must-try dishes Hong Kong” led me to Parkes Road, where two spots, Mak’s Noodle and Mak Man Kee Noodle Shop, serve equally tasty wonton beef brisket incorporating delicious broth, addictive wontons, al dente noodles and moist braised meat.

At Mak Man Kee, I also ordered Chinese broccoli in oyster sauce, and a superlative dish of tender scallions. Despite looking like nothing more than a little side plate covered in a neat array of green onions, the flavour blew me away. They weren’t overpowering like raw scallions in North America but more like thick chives.

An onion is rarely something to write home about, but Mak Man Kee’s dish is a perfect example of how the best epicurean adventures are about being surprised, regardless of cost.

Whatever methods we use to uncover these secret spots, we are all seeking havens of authenticity on an ever-shrinking planet, destinations where everything comes together in one perfect bite.

On the ground

Hong Kong Foodie Tasting Tour

This outfit guides hungry groups through local haunts in Sham Shui Po, Sheung Wan and more. www.hongkongfoodietours.com

Leung Kee

In the middle of Sai Wan Ho Market, Leung Kee is a local favourite for fresh seafood dishes. 12 Tai On St.

Mak’s Noodle

Along with the neighbouring Mak Man Kee Noodle Shop at 51 Parkes Rd., this spot at 55 Parkes Rd. is known for its wonton beef brisket.

Openrice.com

HK insiders swear by this website for restaurant reviews. www.openrice.com

Sheung Hing Chiu Chow

Options at this Hong Kong institution range from a $5 crispy noodle cake topped with sugar and vinegar, to $500 snails from the South China Sea. 29 Queen’s Rd. W.

T’ang Court

The renowned two-Michelin-starred dining room often makes it onto lists of the world’s top restaurants. www.hongkong.langhamhotels.com

Yung Kee Restaurant

This is a go-to spot for meat dishes like roast goose. www.yungkee.com.hk

This story originally appeared in the March 2015 issue of Globe Style Advisor. To download the magazine's free iPad app, visit tgam.ca/styleadvisor.