Dr. Andy Robinson, Animal Biosciences professor at the University of Guelph, is seen with miniature donkeys he uses to teach students remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic, on Oct. 24, 2020.Justin Langille/The Globe and Mail

On a Wednesday in mid-October, Andy Robinson, an animal biosciences professor at the University of Guelph, ran into a snag right before class. Like other instructors affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, he was scheduled to teach his biology course remotely.

But then came a power outage at his home outside Cambridge, Ont. And his internet? Gone.

Luckily, Prof. Robinson had one last option: His cellphone. With just enough signal to connect to Zoom, he shot a live video for his students from his hobby farm’s barn, where he keeps nine miniature donkeys with names such as Anakin, Dexter and Beans.

“So, I basically stood in the donkey barn and talked about the donkeys,” he says now, explaining that most of his students know little about the unusual animals before taking his classes, even those who grew up on farms. “The show must go on no matter what, right?”

Dr. Robinson’s story shows that ingenuity and flexibility are paving the way toward high-quality education even in the face of a pandemic.Justin Langille/The Globe and Mail

As universities across Canada approach the final months of the fall semester, they’ve addressed a school season unlike any other. To prioritize health and safety, most classes have gone online. As have frosh orientation weeks and graduation commencement ceremonies. Residence buildings sit empty or have welcomed only a handful of students.

Yet, as Prof. Robinson’s story shows, ingenuity and flexibility – not to mention a fair amount of digital moxie – are paving the way toward high-quality education even in the face of a worldwide pandemic.

Mary Wilson, vice-provost of teaching and learning at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ont., says she’s been amazed by how universities have stepped up to create a digital learning environment that works.

“Over all, it has been remarkable. It’s to the credit of the entire postsecondary system that we were able to ensure continuity of education for our students and to do it with such concern and quality,” she says.

Creating that continuity has also meant coming up with solutions to keep students, professors and staff safe while still ensuring students can enjoy their university experience. For instance, Brandon University’s music school in Brandon, Man., has invested in high-quality microphones to live-stream music classes and graduation recitals. Sackville, N.B.'s Mount Allison University has changed its academic calendar dates to give students from outside the Atlantic bubble time to self-isolate before returning to class after the holidays. At Emily Carr University of Art + Design in Vancouver, 70 per cent of classes are conducted online only, while the remaining 30 per cent combine in-person and online work.

A miniature donkey grazes on the lawn of Camar Farm near Cambridge, Ont. on Oct. 24, 2020.Justin Langille/The Globe and Mail

At the University of Waterloo, in Waterloo Ont., the school’s co-op program has had to be more flexible with graduation requirements and it’s offering options for shorter work terms. Sophia Potter, a fourth-year urban planning student who is living in residence because the internet is better there than back home, now has a co-op position with the City of Mississauga. She admits finding co-op placements has been stressful.

“It was definitely a big relief when I got this job,” she says.

Meanwhile, Ryerson University in Toronto introduced a new free elective credit course in the summer called Thriving in Action. It combines tips on time management and studying in a digital setting with mindfulness lessons.

Ryerson’s Kristopher Alexander, a professor at the school’s RTA School of Media who teaches video game design, has long used technology to engage students. He’s been combining asynchronous instruction – think videos shot in advance so students can watch them when it’s most convenient for them – with synchronous learning in real time, for years. Either way, his online lessons are simply exciting.

Dr. Robinson says very few students knew about this unique animal before taking his class.Justin Langille/The Globe and Mail

“For those of you new to our show … I mean, class,” he quips during one video game design course he live-streams on the platform Twitch. He’s projected onscreen in a computer-simulated lecture hall he created for virtual classes.

No Zoom fatigue here.

“I aspire to be the teacher that I wish I had,” Prof. Alexander says, sounding just as revved over the phone as he does in his videos.

He explains that because he was already ahead of the curve in terms of digital instruction, the pandemic hasn’t actually changed much for him, although it did force him to research solutions to make the hands-on portion work better. For example, one of his classes requires a student to play a new game in front of peers. After a lot of experimentation, that student can now remotely control the play happening on Prof. Alexander’s own computer.

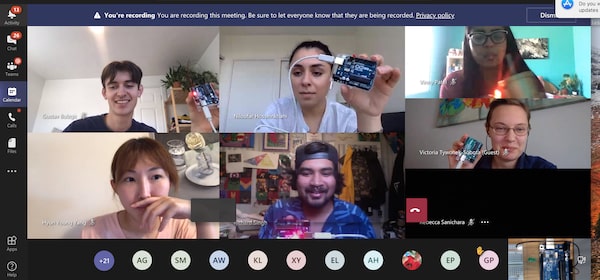

Physical Computing 1: Kinetics online class conducted by a professor at the Ontario College of Art & Design University.Simone Jones/The Globe and Mail

But the pandemic restrictions on in-person communication have also forced professors to find new ways to communicate with their students. Prof. Alexander says when he uses Discord, (“Like Skype, but for gamers,” he explains) his students get excited. Not only does he speak their language but he uses the same gizmos. He’s not just a professor, but a globally ranked gamer who happens to have a PhD.

"The students see all that and they’re like, ‘Wait a second, he’s just like us,’ " he says.

Simone Jones, an art professor at the Ontario College of Art & Design University in Toronto, known as OCAD U, agrees that online learning has had a paradoxically positive effect on the sense of community her students experience. She teaches classes from her own Toronto studio, so they get a window into her world.

“They get a chance to see my life as an artist, which they normally would never see because I would just be standing there in front of them as their professor,” she says. “[Professors are] showing their students that they’re human beings, they’re artists and we’re all in this together.”

Justin Langille/The Globe and Mail

Creating community for first-year students has been one of the biggest challenges for many universities. So, when Gabriella Sunario, a fourth-year University of British Columbia student in Vancouver, started co-ordinating this year’s virtual orientation for frosh, she admits she initially didn’t have high hopes.

“But things worked out better than expected,” she says now, explaining she’s still in contact with some first-year students who signed up for Jump Start activities online the week before school started.

Even so, she’s looking forward to the day when she gets to be in a real classroom again.

“I’m starting my minor in commerce this year and meeting new people I’ve never seen before,” she says. “I’m just excited to see all these new friends in person.”